by Diana

There are themes that occur time and time again during Alexander Technique (AT) classes, and one of these is our concept of stability.

It’s my observation that most people want to feel stable, but they equate the feeling of stability with a sense of being solid, and rigid. Their concept of stability is reflected in the way they move, and in the movements they choose to restrict.

Our ideas and beliefs

We pick up all sorts of ideas as we go through life. We have ideas and beliefs that are reflected in the movements that an Alexander Technique teacher will observe during a lesson. I have encountered students whose ideas of creating a sense—a feeling—of stability means locking their knees, or sticking their head forward and keeping it there, or even restricting movement in every part of their body. If that sounds like a lot of effort, it is!

One student I worked with years ago chose as the subject of her lesson the activity of standing as if to work at a table. I noticed that part of her protocol for ‘standing in front of the table’ involved hyperextending her knees—effectively locking them into a fixed position. I asked what she noticed about the way she stood at the table, and when we talked about what she was doing with her knees she explained that she locked her knees so that she wouldn’t fall over. Again, we seemed to have stumbled across (no pun intended) someone’s idea of stability.

What is stability?

The question is what do we mean by ‘stability’? And I think the answer, for most of us, is that we don’t want to fall over. And we don’t want to feel like we might fall over.

What causes us to fall is a loss of balance. Sometimes that might be due to something within the body – a problem with the inner ear, for example. If this is the case, then AT won’t help you, but nor will tensing all of your muscles to try and stay upright. You need a medical solution.

But in the absence of injury or disease, assuming our normal balance systems are functioning, what usually unbalances us is something unexpected in the environment – a shift of the ground, or of the object that we’re standing on; an unexpected obstacle in our path that we haven’t accounted for; a miscalculation leading us to think we can reach further than we actually can, etc.

The role of flexibility

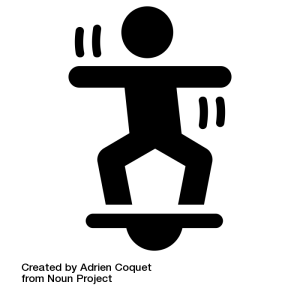

I would argue that flexibility is our best ally in righting ourselves when these perturbations occur. If you’ve tried to create a false sense of stability by locking yourself into place, you will find it more difficult to access the movements we naturally make when suddenly called to right ourselves – the spreading of the arms to balance our centre of mass, the flexing in the leg joints to lower that same centre of mass. It is the ability to access these movements quickly that really gives us stability. Maintaining flexibility, even if it feels less stable, is what will actually help us to adapt to those changes that might topple us.

Feelings are an unreliable guide

I’ve talked a lot about feelings in this post—what we do to feel stable, or to create a ‘feeling sense’ of stability. But just because we feel something, it doesn’t make it true. FM talked a lot about the unreliability of feelings. During his experiments he realised that there were times that not only had he not done what he intended to do, but sometimes he even did the opposite of what he intended, despite his ‘feeling sense’ that he had carried out his activity as intended. This is also a phenomenon we see in the classroom.

The belief is very generally held that if only we are told what to do … we can do it, and that if we feel we are doing it, all is well. All my experience, however, goes to shew that this belief is a delusion.

F. M. Alexander, The Use of the Self (1932)

Aligning our beliefs with reality

To return to my student who wanted to work while standing at the table, and who did so while locking her knees so that she wouldn’t fall over: after we’d worked together and she had rediscovered some of her flexibility, she no longer locked her knees when standing at her work table. I observed her standing comfortably, her natural movement less restricted, and asked her whether she had, in fact, fallen over. She thought long and hard about the question before answering “I don’t know.”

I do not tell that story as any reflection on that particular student. We all of us, me included, have beliefs that do not stand up to rational scrutiny. Rather, I tell that story as a testament to the power of beliefs. That student believed that locking her knees was a necessary condition to remain standing. When we got rid of that ‘necessary’ condition, and she was still standing, she couldn’t in that moment reconcile her belief with the available facts. She answered honestly: she really did not know whether or not she had fallen over.

We all have ideas and beliefs that underlie the ways we choose to move (or choose to restrict movement). If you come to an AT class, it is likely that your ideas and beliefs will be tested, and you may have to choose between a favourite belief, and the facts that disprove it. Alexander’s principles are based on a process of reasoning. Whilst we will always have ideas and beliefs that drive us, it makes sense to try and align those beliefs with reality. When it comes to achieving stability, replacing rigidity with flexibility will get you far closer to true stability, even if it feels counterintuitive.